|

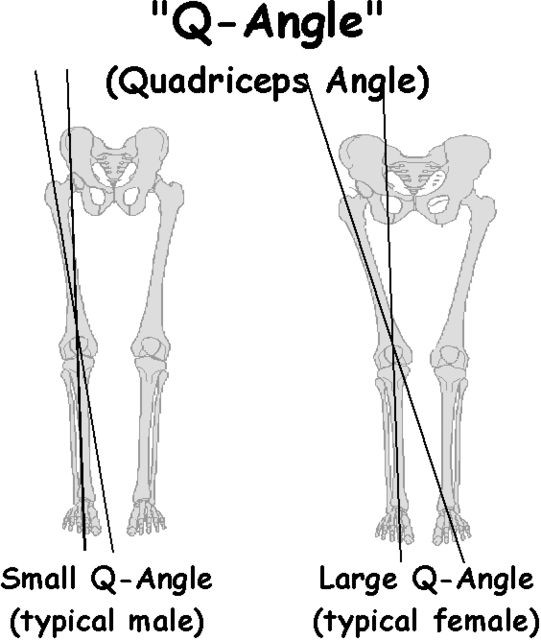

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS) is a common ailment in the athletic population. Incidence rates among adolescent and young adult athletes can exceed 25%, with females more likely to experience it, than their male counterparts.

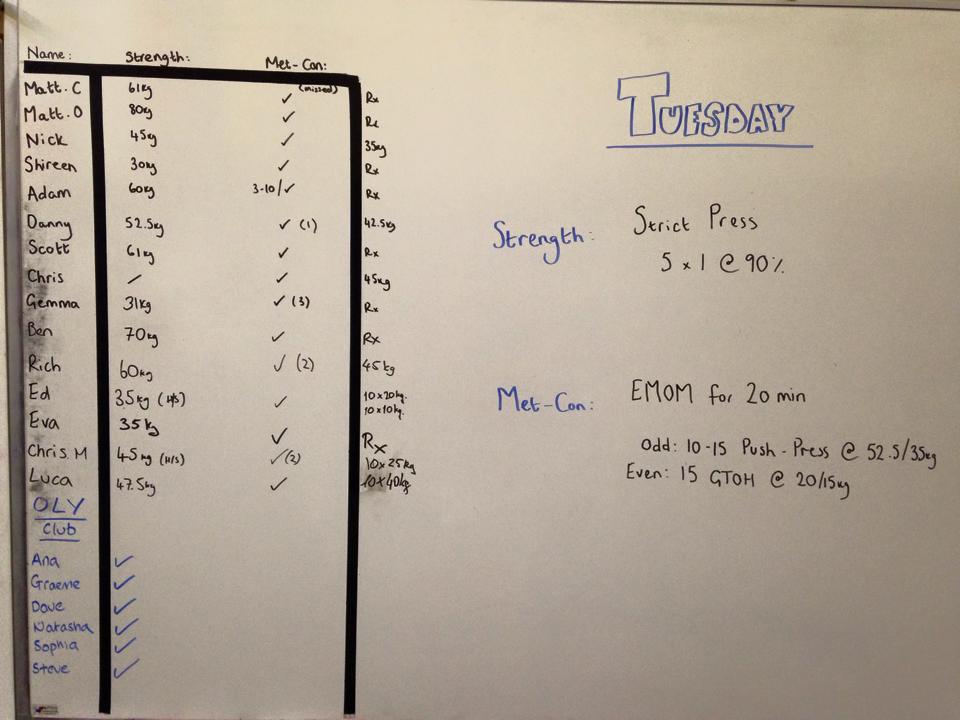

**Disclaimer** PFPS is an actual medical diagnosis and should be made by a medical professional. Self diagnose at your own risk. We will simply refer to general patellofemoral pain (PFP) from here on. There are numerous research studies attempting to explain the causes and most effective treatments for this mysterious, but all too common ailment, including the most recent consensus statement from the British Journal of Sports Medicine. Like many research topics, the information available on PFP seems to be, at times, contradictory and unclear. The purpose of the article is to translate what seems like a jumbled mess of research into something reasonably digestible and applicable to the athlete or coach, regarding the causes and possible treatment of PFP. Causes (Or Effects) of PFP The etiology (cause) is multifactorial. Basically, we do not know exactly what causes it, and several different elements are at play. There is not a sure fire injury mechanism to PFP the way there is with something like a knee ligament tear, and PFP can be present with or without structural wear and tear of the cartilage behind the knee cap. The insidious (gradual and subtle) onset is what makes it such a challenging and confusing issue to deal with; but here is what we have so far:

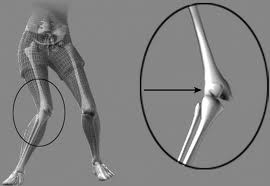

Those experiencing chronic (3 months or more) PFP frequently demonstrated altered kinematics in activities such as walking, running, squatting, and landing from a jump when compared to healthy control groups. Examples include:

Those with PFP also demonstrated movement patterns such as these:

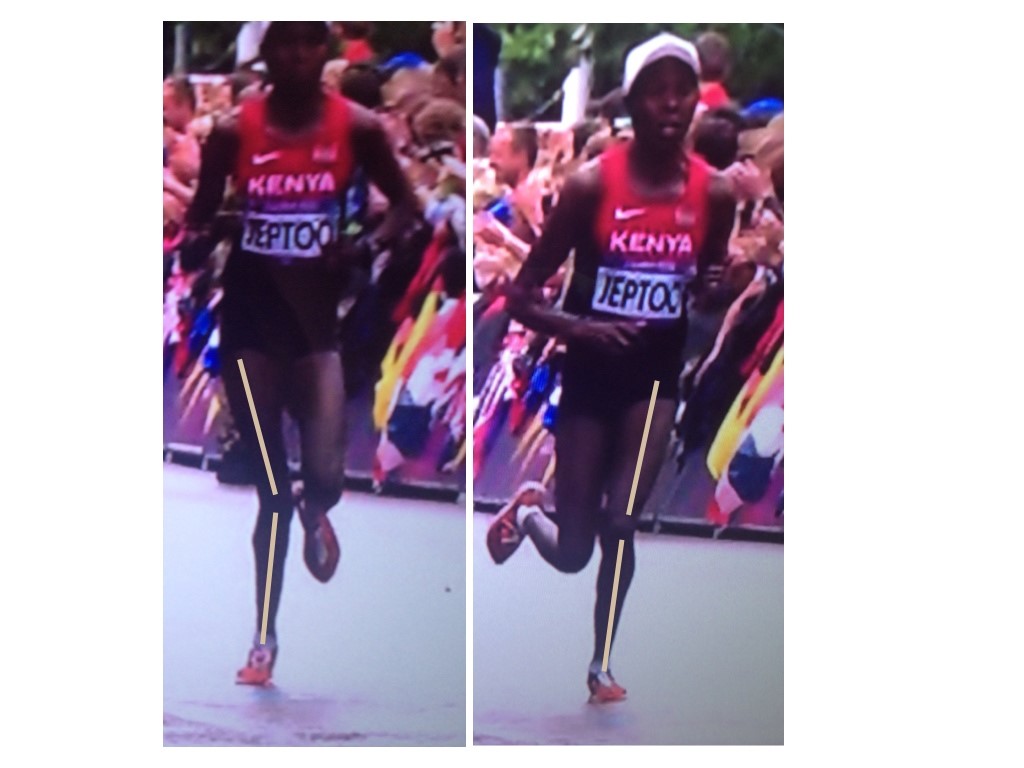

Clearly those with PFP move differently. Sometimes they move more than normal, in one plane, sometimes less than normal. Sometimes fatigue increases alterations in mechanics; sometimes it seems to actually cause a decrease in alteration, as the individual tries to compensate. The complexity is compounded with variables such as pain onset & perception, training age and experience, etc. Yikes. IS THIS CAUSE OR EFFECT? Do the altered mechanics cause the pain or does the pain cause the altered mechanics? We know from pain research that movement patterns change when pain is present, which is consistent with the findings above. We move differently when we are hurt. As for as kinematics being the cause, one study showed that increased hip adduction during running stride was a common trait among female runners that eventually developed PFP (15 out of 400). Neither hip internal rotation or ankle eversion (collapse) was significantly related to those who eventually developed PFP. In another study, 240 healthy young female basketball players were at twice the risk of developing PFP if they demonstrated increased knee valgus forces upon landing from a jump. Certainly this is not enough evidence to say one particular movement pattern is a cause of PFP, but it certainly lends credence to the idea that certain positions and movements seem to be a bit riskier than others; at least in certain populations. We must keep in mind that those two studies looked at adolescent female athletes who participated in specific activities (running and basketball) only. We likely see such varied movement strategies in PFP literature because of the unpredictable nature of chronic pain, as well as the variance in patient population (male vs female, adolescent vs adult) and testing methods that were used. **Take Home Points and Soap Box**

Knee Valgus = PFP cause or effect? Maybe both? Maybe neither? If she has no pain and has won the Boston Marathon 3 times, are you going to intervene? I’m not. If she was 14 with no other athletic experience, it’s probably a different story.

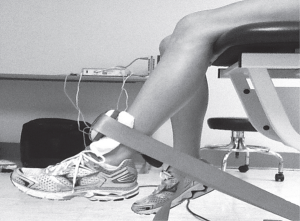

However, strength of these muscles groups was tested in an open chain fashion, such as in the pictures below. This type of voluntary maximum isometric testing does not necessarily mimic the involuntary reflexive demands of these muscle groups during closed chain activities such as squatting, stepping, and jumping activities. This may explain inconsistencies in the research regarding the associations between muscle weakness and movement patterns. Some studies did show association as described above; but others showed such variations as participants having weak hip abductors but not necessarily demonstrating lack of control in the frontal plane, or showing weakness with hip external rotation but not demonstrating abnormal motion in the transverse plane during dynamic activity. So even though all participants with PFP demonstrated weakness in at least one plane of motion, was testing strength in this fashion really getting to the root of the problem, or was it just picking up pain inhibition? Again, chicken or egg. Based on a systematic review done last year of the available literature on the topic, maximal isometric hip strength was NOT a risk factor for PFP. In other words, the weakness that we see in isometric hip strength with those (females especially) who have PFP, is more likely due to the pain itself (a symptom); rather than a contributing cause of the PFP response. What I thought was pretty interesting, however, was that muscle groups that typically tested weak actually showed higher EMG activity during dynamic movements versus healthy individuals. The hypothesis here was that weak muscles were working overtime to try to stabilize and perform the movement. This is consistent with what the great Charlie Weingroff says about EMG – “It doesn’t lie, but it doesn’t tell the whole story”. He uses the example of comparing two people who’s max back squats are both 500lbs. He’s taking the guy who has less EMG activity in the abdominals, as this indicates he is expending less energy and likely has more movement options at his disposal. There was also evidence of delayed timing of certain muscles groups, which seems to hit closer to the root of the issues – reflexive neuromuscular control. Unfortunately, there is little in the way of prospective studies (looking for risk factors) regarding reflexive neuromuscular control **Take Home Points**

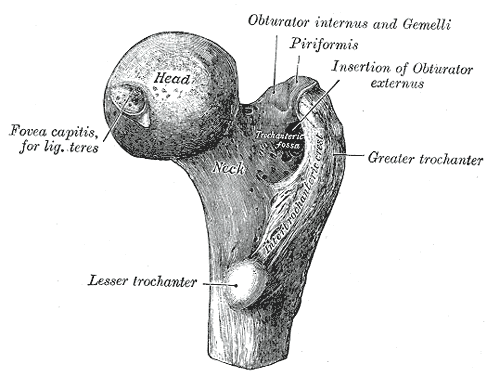

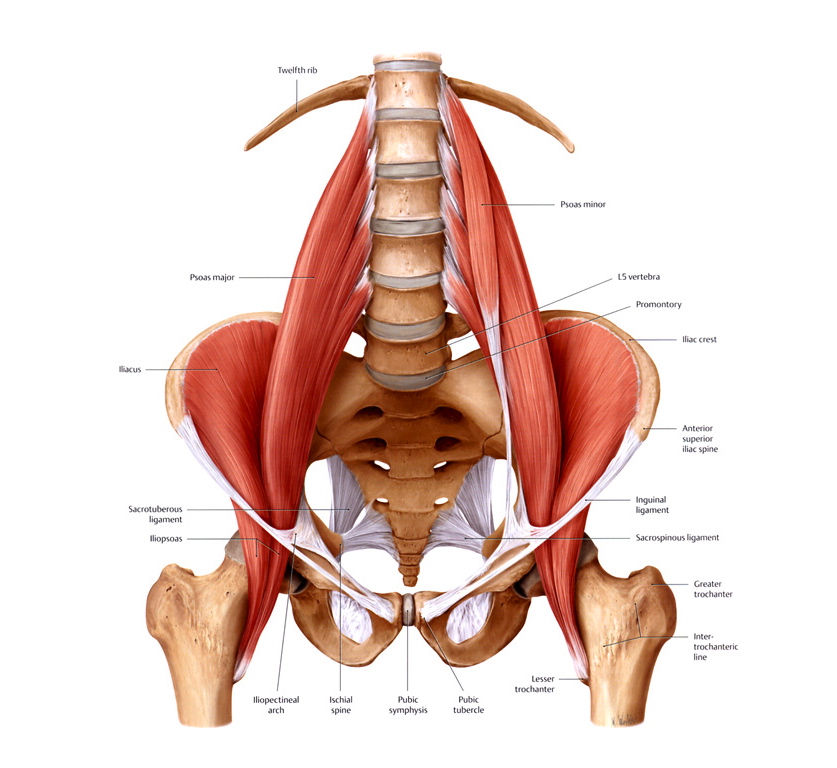

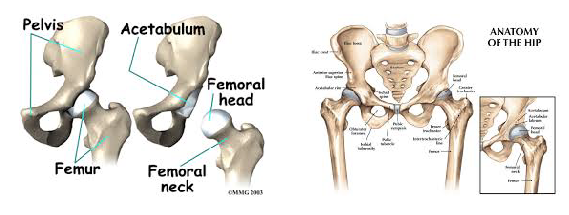

So what do we do about it? Hip & Quad Strengthening In The Open Chain Since weakness of the hips and distal quads was present in many of the participants with PFP, several studies have incorporated strengthening protocols. Some of those protocols involved only exercises that looked like this, being performed at 3 sets of 10 repetitions. The classic, “glute activation” protocol. You are probably laughing. “Typical PT garbage”. How are these worthless open chain exercises going to strengthen muscles or affect a condition that is present in weight bearing patterns? I’m with ya. Except that in pretty much every study, the participants demonstrated greater hip strength and reported less pain! Before we deem it a miracle, let’s talk about it. In many of the papers incorporating these basic exercises, the participants were either sedentary or were recreational runners. So, in other words, they were probably very weak, and these exercises were enough to give them a stimulus and subsequent strength adaptation. The strength testing was in the open chain and the exercises were in the open chain; so that explains the carryover. However, some of the programs implementing these types of things were only 3-4 weeks long. This is not enough time to develop appreciable hypertrophy to explain the increase in force production. The likely explanation here is these exercises improved neuromuscular signaling, so that the participants were better able to recruit motor units and demonstrate the strength that they already possessed. Would a group of highly trained individuals with PFP have responded to the exact same basic protocols as favorably? Hard to say, but probably not. What these exercises did not do was change mechanics or neuromuscular timing during dynamic weight-bearing activities. This is not surprising. So then, how did they help to decrease the patient’s pain? The actual mechanism? We don’t know. There’s always the argument that untrained or recreational-only individuals were simply doing something different that they thought would work, and so it did. Perhaps, by increasing neural drive to the muscles of the hips, regardless of the nature of the activity, this decreased the threat response in the brain – which subsequently decreased pain perception. Like the brain said, “hey things can actually fire down there, so maybe our legs aren’t actually going to fall off every time we go up and down the stairs.” Perhaps the movement variability that the exercises provided gave enough proprioceptive input to the brain that it made all lower extremity activities less threatening, regardless of mechanics. Maybe the “feel-good” hormones that were released with exercise also helped to quell the perception of pain. I would have liked these studies to compare to some type of sham treatment. The use of hip strengthening techniques like the ones above seem to be superior for reducing symptoms when compared to open chain quadriceps strengthening. Quad exercises included: straight leg raises, quad sets, short arc quads, and knee extensions. Those performing these exercises alone also improved, just not to the same extent. And like the open chain hip activities, these basic quad exercises did nothing to alter or improve what were thought to be faulty mechanics during dynamic activity. Hip & Quad Strengthening In The Closed Chain There were also studies that incorporated closed chain strengthening such as variations of squatting, lunges, step up, step downs, single leg hinges balance, etc. The studies had a mix of untrained and trained participants. The participants reported less pain after these more intense regimens as well. They also demonstrated improved hip strength and kinematics during various dynamic activities! Sounds like we have a winner! The issue is that the participants in these studies were also coached through proper biomechanics during the exercises. This is great for real world validity, but it confounds things a bit; as maybe these more complex movement patterns require the proper coaching in order to be effective. Of course this is not necessarily a negative; because if 2 or 3 sessions of movement coaching will yield similar improvements as going to the clinic 3x/week for 6 weeks, I choose the former, with a maintenance corrective program. For the running population, coaching seems to be very effective for improving mechanics and subsequently reducing PFP. They simply cued for symmetry of stride, a relatively level pelvis, forefoot strike, and knees tracking over feet. A mirror was also used, so that the athlete could see what was going on. No banded hip exercises needed, or an intense regime of closed chain exercises. Now, those things could definitely be a part of the home exercise program, but on the client’s time. Then there was the “multi-modal” studies. Basically this means that the participants performed several different flexibility and strengthening exercises, utilized taping techniques, and received various manual therapy techniques. They got better too; but because they used every intervention under the sun, we don’t know what worked. Muscle flexibility was something that was looked at by only a few studies that I saw, but is commonly addressed with PFP. Muscles commonly thought to be “tight” and contributors to PFP are calves, quads, hip flexors, etc. It is difficult to objectively quantify these things in studies, which is probably why they were not included very often. Clinically, I do a whole lot of cranking on people. If they want to do some light stretching on their own, that’s typically fine; but we generally get way more bang for our buck looking at other things. Finally, the use of physical agents (therapeutic modalities) has not shown benefit in patients with PFP compared with controls. Here is a quote from a systematic review: “None of the therapeutic modalities reviewed (ultrasound, iontophoresis, phonophoresis, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, EMG feedback, TENS, laser) has sound scientific justification for the treatment of PFPS when used alone.” I will simply say that this comes as no shock. Summary I started this Part I article by saying the cause of PFP is multifactorial. Combinations of biomechanical, neuromuscular, and autonomic (nociception and pain perception) are all likely contributing factors. The nature of the treatment seems to be the same. We first need to eliminate the aggravating activities if the PFP is causing you to compensate in some way. This does not mean stop training. It means find something else that does not flare you up. Then we address movement patterns. This may be through simple cueing, or may be done by regressing the activity to its subsequent parts, and building positions from the ground up. Drills and neuromuscular tricks can be incorporated to increase the neural drive where we want it, based on the movement pattern that we are trying to build back up. In Part 2, we shall go through a sample protocol outlining all of this. Credited to www.jtsstrength.com The Hip Impingement SolutionINTRODUCTION: As we strive to be more active, healthy and mobile, the hips are put under a large amount of stress. With the increase in functional training, more emphasis is being placed on squatting, lunging, deadlifting and Olympic lifting. Functional exercises are essential in any training program, but for these exercises to be performed correctly, the hips must be able to transfer force from the ground and through the spine. When there is a minor deviation in hip movement, increased friction can occur inside of the joint leading to soreness. Many times after a training session we are experiencing appropriate muscle soreness, which is excellent and needed for increased strength gains. Post exercises soreness should be isolated to muscular tissue in the posterior or lateral hip. If you are experiencing anterior/lateral hip or groin pain the following article should benefit you greatly. Femoral Acetabular Impingement or FAI is becoming a more common pathology identified in the active population due to advancements in diagnostic imaging and clinical assessment. My goal for this article is to educate the reader on the anatomy of the hip, what is FAI, what causes FAI, symptoms of FAI, how to self assess if you are at risk for FAI, and lastly how to address any issues you may be experiencing through a series of corrective exercises. HIP ANATOMY: Before we go any further, it is important to review the anatomy of the hip to ensure we are all speaking the same language as we move into the causes of FAI. The hip joint is a ball and socket joint consisting of the head of the femur (ball) and the acetabulum (socket). Below are two images of hip boney anatomy. In the figure to the left, we can clearly view the head of the femur and the acetabulum, which are surrounded by various ligaments and joint capsule to encompass the “hip joint”. The hip joint is a very complicated joint from a ligament and muscle standpoint secondary to multiple connections from the trunk, shoulder, hip and thigh musculature. For the sake of the topic of this article, we will not dive into all of the ligaments and muscles of the joint, but I would like to point of some key structures which play an important role in this pathology.

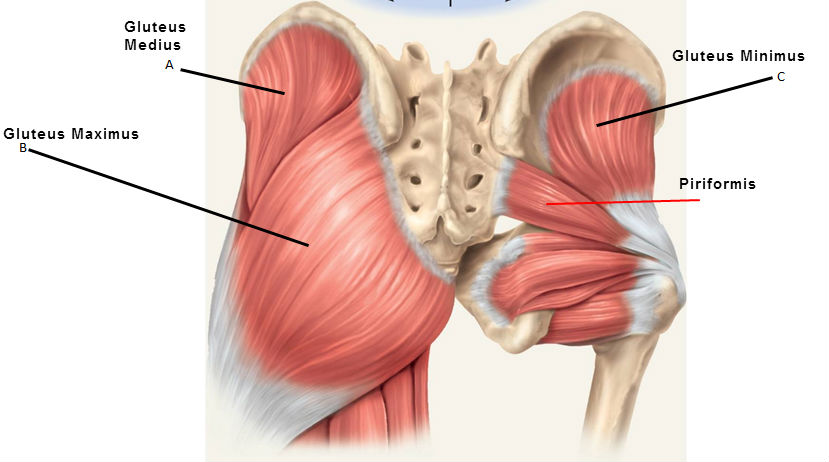

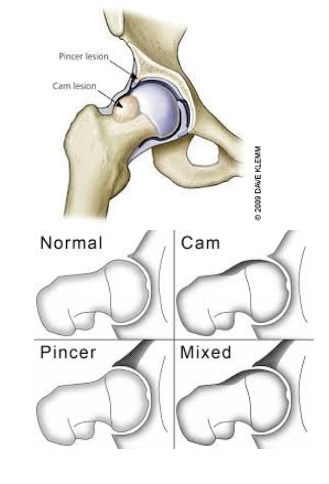

Deep hip external rotators: this muscle group consists of many small muscles that attach from the sacrum (tailbone) to the femur, and act to externally rotate the femur. When these muscles are weak, the knees have a tendency to cave-in (valgus) during a squatting motion. CAUSES: The causes of FAI are currently not completely understood, though it is hypothesized that faulty mechanics during daily activities and squatting can cause excessive compression between the neck/head of the femur and the rim of the acetabulum leading to impingement. When excessive contact between these two structures occur, bone growth can form, which leads to a CAM or Pincer type deformity shown below. A CAM lesion is an abnormal formation of bone growth on the neck/head of the femur, which leads to increased contact between the femur and acetabulum causing a pinch when the hip goes into flexion/adduction/internal rotation. A Pincer lesion is an abnormal formation of bone growth on the outer rim of the acetabulum, which also leads to increased contact between these two structures. While CAM lesions are more common in males, and Pincer lesions more common in females some studies suggest 86% of symptomatic people experience a combination of both deformities. In an attempt to understand what faulty mechanics might possibly cause CAM and Pincer deformities, many studies have identified excessive hip flexion/adduction/internal rotation as the culprit. The image on the left demonstrates a view of how a lesion may appear while the image on the right dictates the classification for each lesion.

It is important to note that though you may be experiencing one or two of these symptoms, you still may not have pathology. Many time symptoms of FAI can be confused and misdiagnosed as a hip flexor or groin strains. If one side feels different than the other, caution must be taken when training into positions of deep squatting, lunging, twisting and higher impact plyometrics without consulting a physical therapist or orthopedic specialist. SELF-ASSESSMENT: In this section we will go over some self assessment techniques to help you determine if your are experiencing symptoms that may be associated with FAI, though these movements are in no way a substitute for a professional clinical examination from an orthopedic specialist, physical therapist, or surgeon. There is a limit to ones ability to perform self-assessment, and an orthopedic specialist will use a variety of special tests and diagnostic testing to ensure an accurate diagnosis.

Hip flexion test: Lye on your back with both legs straight. Pull one knee to your chest without letting your knee rotate to the outside. Note how high you can flex one hip compared to the other. Test is positive if you feel a pinch in the anterior/medial groin or there is a significant difference in range of motion between the two sides. *This is a self-assessment of your hip flexion range of motion. Many times hip flexion range of motion is poor with individuals who are experiencing hip FAI. This is more of a clinical assessment, not a test that has been validated in the research.

*If these tests are positive, it does not mean that you have pathology. These tests will simply identify movements, which cause impingement in the hip. To get an accurate diagnosis of your pain, an orthopedic specialist or surgeon should be consulted. ACTIVITY MODIFICATION While no one likes to change what they are doing in their normally daily routine, research has been shown to significantly decrease FAI hip pain with simply changing daily habits that may be contributing to continued irritation. Below is a list of activity modifications that should be performed if you are experiencing above stated signs and symptoms:

These activities should be modified until symptoms are completely reduced. Once symptoms are eliminated, caution should be taken when returning to normal activities. STRETCHING Stretching and regaining normal range of motion and flexibility is extremely important when addressing deficits related to FAI. I would caution from “over stretching” the hip as this can cause irritation within the joint. Extreme caution must be considered when performing below stretches. Stretching for hip FAI includes the use of an elastic band, as the elastic band will help create slight traction in the joint; therefore, decreasing the risk of impingement and increasing the stretch of the tissue being addressed. Stretching performed prior to a training session should be dynamic and be held no longer than 5 seconds, while stretching post training should be held for duration of 20-60 seconds based on age (longer holds for increased age). All stretches should be performed for 2-3 sets for optimal flexibility gains.

While not all of these stretches will need to be performed daily, areas of tightness are going to need to be addressed to make significant gains. If the Thomas test above was positive, more attention is needed to the quads and hip flexor. If the hip flexion assessment listed above was significantly different than the non-involved side, pay more attention to the hip flexion stretch. The glute and adductor stretch are great for preparing the hip for the sumo squat position listed below. If any soreness or pain is felt with stretching, be sure to immediately stop that given stretch. Do not try to push through any discomfort with these stretches, and contact your local physical therapist or orthopedic specialist if you are experiencing negative results with the above listed stretches. CORRECTIVE EXERCISES: Corrective exercises are just that, corrective. These exercises are not huge strengthening exercises, especially in the beginning phases as proper muscle activation needs to be achieved before advancing to more functional positions. These exercises are broken up into 3 phases and are intended to ensure proper muscle activation in phase 1, increased difficulty in phase 2, and muscle hardening in phase 3. All of the exercises listed below or intended to decrease the tendency for the hip to obtain the position of flexion/adduction/internal rotation, which we now understand from research are the compromising positions of hip FAI. Each phase has a purpose and should not be skipped or overlooked. An individual can move on to the next phase when the appropriate sets and reps are met with minimal fatigue, perfect form, appropriate muscle activation, and no pain with any exercise. *For exercises not pictured below, a quick google search will do the trick. Pictured below are the less commonly understood exercises. PHASE 1 (3x20reps)

PHASE 2 (3x15reps)

PHASE 3 (3×8-10reps)

Incorporating these exercises into your daily routine is going to be a huge part of being successful in addressing hip FAI. If performed correctly, these phases can be progressed through in 1-2 week blocks. Once you have completed the final phase, incorporate as many phase 3 lifts as you can into your normal training routine. Review your training with your strength coach to come up with the best possible program. I would also encourage performing phase 1 exercises (1 set) prior to heavy squatting days to ensure your hips are properly activated prior to loading. Stretching can be continued throughout life as staying mobile in your hips will allow for full movement and continued strength gains throughout your training. I hope the above information has helped open your eyes to an increasing common pathology that has been surfacing in the Olympic lifting and Cross Fit community. As previously discussed, if you are experiencing pain with the above listed stretches or exercises, please stop them immediately. If you continue to experience hip pain you should schedule an appointment with your local physical therapist or orthopedic specialist to undergo a thorough evaluation of your condition. Hip pain can arise from many different pathologies, and hip FAI should be considered if there is continued anterior hip pinching felt with daily activities or after training. Credited to www.jtsstrength.com |

AuthorCrossfit RNA Categories

All

Archives

May 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed